Doing the groundwork: Monika Mondal wins our environmental prize

PROFILE: Young Journalist Award 2021 (environment) winner

It’s hard to believe that Monika Mondal only started her journalism career last year at the height of the pandemic with no formal training. She was previously a yoga teacher, prior to that, she was in engineering.

“I always wanted to speak up against the powerful, but I was always too shy and I lacked confidence,” she remembers. “Then I just decided that I would do whatever I wanted to do without overthinking it.”

Monika’s growing body of work has already won recognition in India. “Shandaar”, the Hindi word for “magnificent”, was a word used by respected Indian journalist, Ravish Kumar, to describe a story she had written. So thrilled was Monika of his acknowledgment back in the summer that she proudly displays his comment as a pinned tweet on her Twitter profile.

But while 28-year-old Monika may have managed to chart a new course, life for her has been a harsh and grinding reality. Growing up in a small urban slum on the outskirts of New Delhi, India, she has survived testing conditions, both physical and mental.

“I grew up in one of the poorest, most uneducated and unhygienic parts of New Delhi,” she says. “For a large part of my life, I tried to hide this because, from past experiences, I thought people would judge me as being uncivilised.

“But being a slum dweller does not make anyone any less of a person. Slum residents are valid inhabitants of the city entitled to enjoy a safe and healthy environment. Looking back, I think I'd never have found my passion, journalism, if I hadn’t grown up here.”

From the outset Monika has gravitated towards social affairs. As for the environment, it was a coincidental genre.

“I often joke about this and say because I was born on World Environment Day, 5th June, it is my duty to cover the environment. But honestly, when I started to report, I did not think about choosing a genre,” she says. “I just wanted to write about the things that really moved me and mattered to me. Somehow, most of the stories I write about are connected to the environment, agriculture and climate – and the injustices therein.”

Monika’s work is the painstaking accumulation of detail about how business practices play out in the lives of ordinary people. In February, 2021, she travelled to the Uttar Pradesh town of Khatauli to talk to villagers who claimed to have been affected by wastewater released by the Triveni Sugar Mill, the largest in Asia.

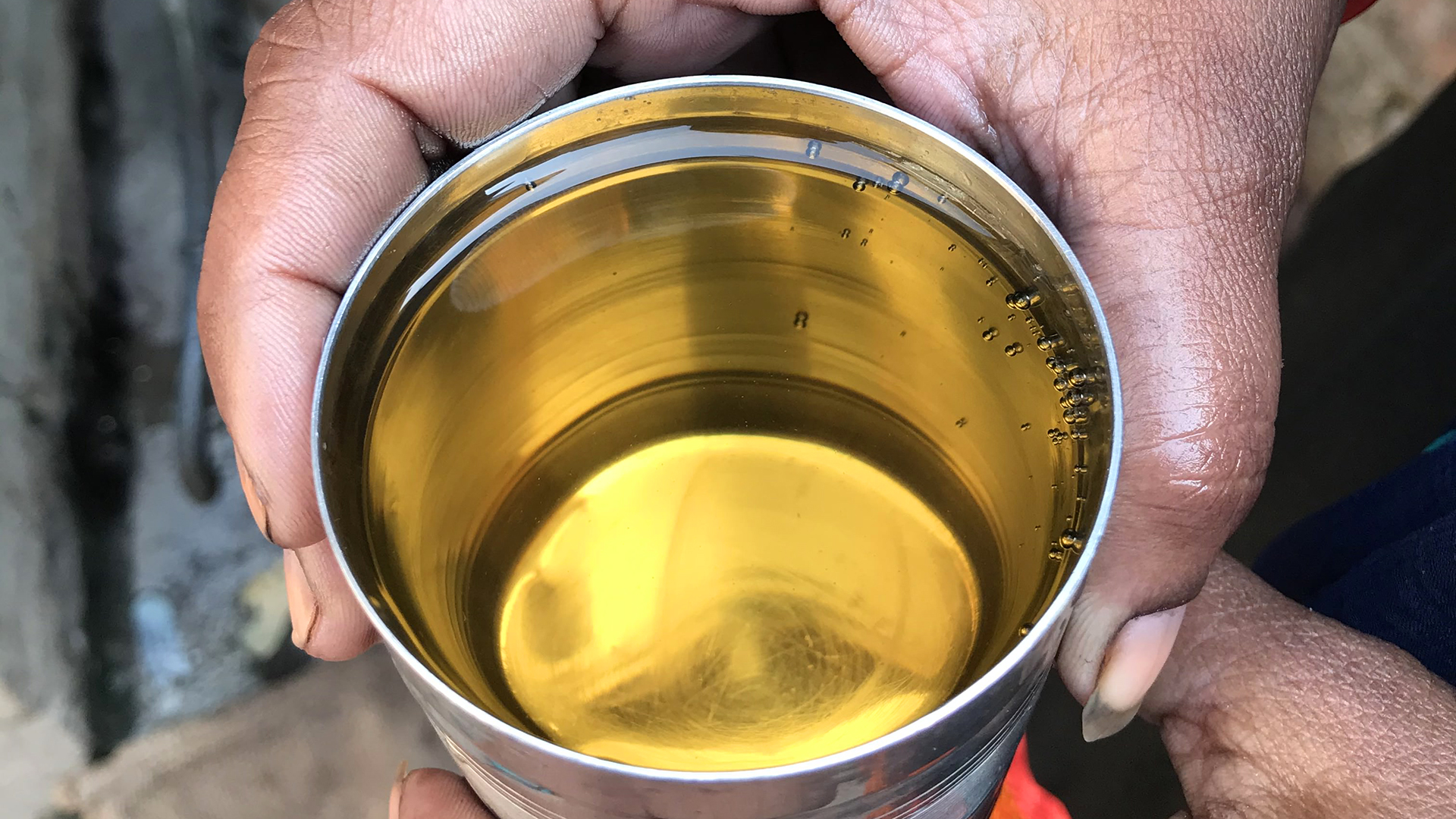

After spending two days with local residents, Monika was ready to pitch her story into the hidden water crisis behind India’s sugar dominance. It wasn’t long before she was back collecting water samples from the ground and from households, interviewing company officials and health experts and running lab tests for The Third Pole – a multilingual platform covering issues around water, climate and nature in Asia. The results were “shocking” and “stark” and she explains how those tasked with protecting the environment and the health of the people were turning a blind eye.

Four months after her first visit to Khatauli, Monika was ready to present her findings: “Villagers living in the Uttar Pradesh sugar belt have been bearing the brunt of poorly implemented environmental regulations and water scarcity,” she wrote in her piece for The Third Pole.

“The sugar industry is a key part of India’s agrarian economy. It sustains areas such as Khatauli and supports both the farmers and the community at large. However, a fast-degrading environment and deteriorating water sources are undoing years of economic progress, threatening the health and wellbeing of thousands of people.”

Time will tell if there are any permanent answers, but for Monika, the biggest impact of her story is that she could give meaning and shape to frustration and searing inequality and bring to the world's attention voices that weren’t heard. “Those who had been narrating their sufferings to me had realised that their cries for safe water were not worthless,” she says.

“I still receive calls from villagers with the same complaints. They think I have the power to bring clean and safe water to their doorsteps. I am almost as helpless and powerless as they are, but it feels good to know that they have opened up to me and are willing to share their plight.”

Monika’s ambitious and revealing investigation, which runs to 4,000 words, has now become a legal case in India’s environmental courts. Independent groundwater testing in Khatauli is currently underway by court officials.

Her story was chosen for a special, one-off environmental prize as part of this year’s Thomson Foundation Young Journalist Award. Out of some 300 stories covering climate change and biodiversity, spanning 55 countries and four continents, the story was selected by the judges for “delivering on everything you want from a groundbreaking, fresh and memorable piece of environmental journalism”.

Judging the award were Caro Kriel, chief executive of Thomson Foundation, Patrick Greenfield, environment and biodiversity reporter for The Guardian and Leo Hickman, director of Carbon Brief. Monika’s work was praised for showing “maturity” and a “compelling human element.” It left a lasting impression on Patrick who said he spent “a whole lot of time thinking about it after”.

In her late twenties, Monika seems to have found her vocation. As the editor of her winning story, Lou Del Bello, remarks: “Monika is one of the most talented young journalists I know, fighting the good fight. She gives me hope for the future.”

Read Monika’s award-winning piece here.

The environment needs all of us because we need the environment.

Monika has advice for young journalists:

“Stand with the voiceless and powerless, highlight the truth and hold the powerful accountable. It's not only the best time to be an environmental journalist, it's also very critical. It’s the need of the hour. The environment needs all of us because we need the environment.”

Acknowledgements:

Monika, together with Kai Hui Wong from Malaysia, this year’s winner of the Young Journalist Award, and two runners up, Tatiana Pardo Ibarra from Colombia and Mahima Jain from India, will receive £1,000 learning bursaries or funds to buy equipment.

We would also like to congratulate the following young journalists for making it into the environmental shortlist:

Carmen Valeria Escobar Castillo, El Salvador; Julia Dolce, Brazil; Raqib Hameed Naik, Kashmir; Ifeoluwa Adediran, Nigeria; Juan José Relmucao, Argentina; Ishan Kukreti, India; Tatiana Pardo Ibarra, Colombia; Helena Carpio, Venezuela; Ismario Rodriguez Pérez, Cuba; Gëzim Hilaj, Albania; Devyani Nighoskar, India; Kabir Adejumo, Nigeria; Mohammed El Said, Egypt; Damilola Ayeni, Nigeria.

You can see their shortlisted stories here.

Young Journalist Award: Environment

Established in 2013, the Thomson Foundation Young Journalist Award – in partnership with the UK Foreign Press Association (FPA) – pays homage to emerging journalists, 30 years of age and under, addressing some of the most important social and political issues of our time.

An environmental category was introduced to this year’s award in response to COP26 and the urgent fight to tackle global warming. All entrants were asked to submit a portfolio of three stories, including at least one story with an environmental reporting focus.

The Young Journalist Award will reopen in July, 2022.